1968: learning politics as a student

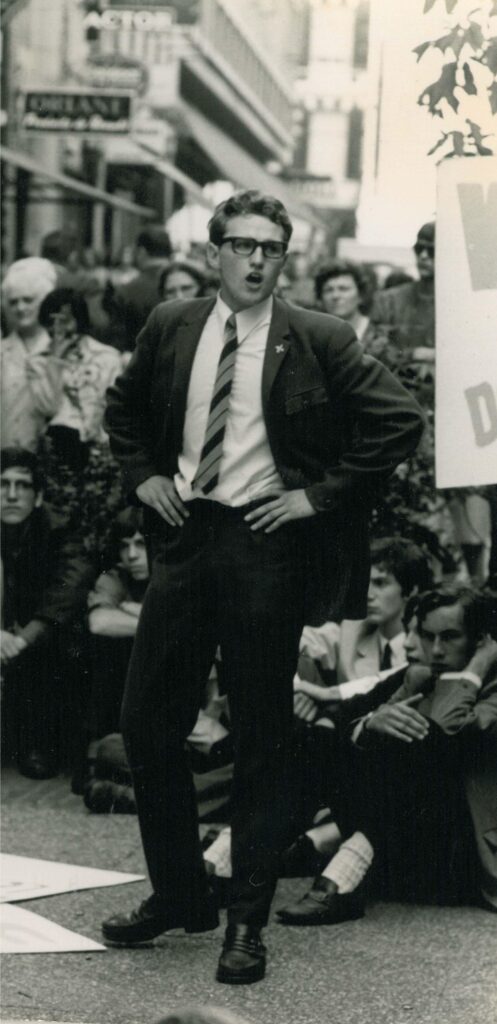

In 1968 I was a student, and like many of my generation I was swept up in a moment when history seemed unusually open. I still have a photograph from that year: I am standing in a market square, speaking to passers-by about the need for change and for a fairer world. It was not an abstract exercise. The late 1960s were marked by intense power struggles that felt immediate and existential.

The Vietnam War exposed the limits of political legitimacy. The civil rights movement in the United States challenged entrenched racial domination. Decolonisation was reshaping global power relations, often violently. Student movements across Europe questioned authority, hierarchy and inherited privilege. The Cold War and the constant shadow of nuclear conflict underscored how concentrated power could threaten humanity itself.

Even then, what troubled me most was not only injustice, but powerlessness. Who decided? In whose interests? And how could ordinary people meaningfully influence the systems that governed their lives?

At the time, I did not yet have a conceptual framework for these questions. That came much later.

Freedom, power and an old philosophical tradition

Over the years, I came to understand that many of the questions raised in 1968 were not new. They had deep philosophical roots. One of the earliest and most influential treatments appears in Plato’s Republic, where political order, justice and the organisation of economic life are treated as inseparable. Freedom, for Plato, was never simply individual licence; it was bound up with the structure of the polis and the distribution of power within it.

This line of thinking later developed into the republican tradition. In that tradition, freedom is not defined as the absence of interference, but as the absence of domination. You are unfree if you live at the mercy of another’s will, even if that power is exercised kindly or infrequently. Dependence itself is the problem.

Economic republicanism extends this insight from politics into the economy. It argues that political rights alone are insufficient if people lack power over the economic structures that shape their lives: work, housing, energy, finance and, increasingly, digital systems. Without such power, freedom exists only by permission.

This also links directly to sovereignty. Not just national sovereignty, but personal and collective sovereignty: the capacity to shape the conditions under which one lives rather than merely adapting to them.

Discovering the internet early: 1978 and a different perspective

My first encounter with what we now call the internet dates back to 1978, when I had just set up my own business in the Netherlands. At that time, almost everyone involved was a technologist. The focus was on hardware, protocols and engineering challenges.

What struck me immediately was that the real transformation would not come from the technology itself, but from what could be built on top of it. I approached the internet from a business and societal perspective rather than a purely technical one. Applications, services and new forms of interaction mattered far more than the underlying infrastructure.

This approach proved successful in the Netherlands, and in 1983 I introduced the same thinking in Australia. That coincided with the introduction of Viatel, one of the first public online services in the country. Even then, I saw networked technology as a public service and as an enabler: a foundation for education, commerce, communication and community-building.

Social democracy, broadband and renewed optimism

I have always identified with social democratic values. For much of the post-war period, social democracy delivered rising living standards, strong public institutions and a workable balance between markets and democratic control. By the late 1980s and 1990s, however, that balance was beginning to erode.

The spread of the internet and broadband rekindled my optimism. I believed these technologies could democratise access to information, reduce asymmetries of power and strengthen civic participation. Knowledge could become more widely distributed. Communities could organise more effectively. Decision-making could become more transparent.

This belief shaped much of my professional work. I became involved in broadband policy in several countries around the world, consistently arguing that broadband should not be judged by speed or coverage alone, but by what it enabled: e-education, e-health, smart energy, smart cities and broader digital participation.

The UN Broadband Commission and global digital development

This thinking culminated in 2009, when I became a co-initiator of the UN Broadband Commission for Digital Development. The Commission’s core aim was explicitly political in the republican sense: to spread the empowering potential of broadband beyond Western economies.

The argument was straightforward. Broadband infrastructure, relative to its benefits, is comparatively low cost. Properly deployed, it could accelerate education, improve health outcomes, support economic development and strengthen institutional capacity in non-Western societies. In short, it could help lift societies and economies by giving people access to knowledge, services and markets that had previously been beyond reach.

The Commission deliberately framed broadband as an enabling infrastructure, not a luxury technology. Power lay not in the cables themselves, but in what communities could do with them.

Smart energy and smart cities as empowerment projects

In 2001, my work expanded into smart energy. Again, the goal was not technological novelty, but user empowerment. New communication infrastructure and application software made it possible for people to gain insight into, and control over, their own energy use. Energy could shift from something imposed on consumers to something they could actively manage.

From 2005 onwards, I became deeply involved in smart cities. Not smart cities in the narrow sense of sensors and dashboards, but as a way of using technology to enable bottom-up democratic empowerment. Cities seemed to me the most promising scale at which to rebalance power: close enough to citizens to matter, yet large enough to shape infrastructure, services and planning.

Smart cities did not deliver all the outcomes I had hoped for, but they did demonstrate that local, participatory approaches could shift power incrementally. They also reinforced a hard lesson: technology alone does not democratise power. Without institutional design, democratic oversight and economic constraints, technology often reinforces existing hierarchies.

Platforms, advertising and the concentration of power

A decisive turning point came with the rise of large digital platforms. In the early 2000s, search engines and social platforms were still experimenting with business models. By the mid-2000s, roughly between 2003 and 2007, advertising became dominant.

Advertising rewarded scale, attention capture and behavioural profiling. Growth became the overriding objective. Power concentrated rapidly in the hands of platform owners. Users became inputs into monetisation systems rather than participants in shared digital spaces.

From a very early stage, I publicly argued for permission-based marketing. The idea was simple: users should retain control over how their data, attention and participation were used. Advertising, if it existed at all, should be based on informed user choice rather than extraction.

This was an attempt to embed a republican principle into the digital economy. It failed. The advertising model proved too profitable, and power concentrated further.

AI, sovereignty and hard-earned scepticism

Today, AI presents itself as the next great transformation. I still see enormous potential, particularly in education, health, energy management and public administration. But I am no longer naïve.

I have learned from the internet, from platforms and from social media. Without deliberate intervention, AI will follow the same trajectory: concentration of power, increased dependency and reduced sovereignty. Only faster.

The core question is not whether AI is powerful, but who governs it, who benefits from it and who becomes structurally dependent on it.

Crisis, change and unfinished work

On darker days, I suspect that societies only rebalance power through crisis. History offers many examples: the Great Depression, the Second World War, the upheavals of the 1960s. Each disrupted entrenched structures and created space for reform.

I hope we can avoid repeating that pattern. But I see little evidence of common sense prevailing at scale. Muddling through may stabilise systems temporarily, but it rarely redistributes power.

Economic republicanism nonetheless offers a form of grounded realism. Power is not reclaimed in a single moment. It is built through institutions, norms and incremental shifts. Cities, communities, infrastructure choices and digital governance still matter.

See: Care economies – a way out of the neoliberal collapse

Looking back, looking forward

When I look back across more than half a century – from my student days in 1968 to today’s debates about artificial intelligence – what stands out is not a steady march of progress, but a recurring pattern: moments of promise followed by the re-concentration of power.

Again and again, new ideas and new technologies appeared to open space for broader participation. Expanded education, social democracy, broadband, the early internet, smart energy, smart cities. Each offered the possibility of rebalancing influence between citizens, institutions and markets. Yet time and again, the political and economic structures surrounding these innovations enabled the already powerful to consolidate their position. What began as an opportunity for empowerment became, often quietly and efficiently, a mechanism for control.

This was not accidental. Contemporary political systems increasingly reward scale, capital concentration and regulatory capture. Markets favour those who can externalise costs. Platforms grow by extracting value from participation while denying participants real agency. Public institutions, hollowed out over decades, struggle to restrain private power and too often end up reinforcing it. The result is a form of managed freedom: access without leverage, choice without influence, participation without sovereignty.

Technology has played a central role in this story, but never as an autonomous force. Infrastructure does not distribute power by itself. It reflects the intentions, incentives and constraints of those who design and govern it. Broadband can democratise knowledge or centralise surveillance. Platforms can support communities or hollow them out. AI can extend human capability or entrench new hierarchies at unprecedented speed.

What I have learned is that freedom without power is fragile. It can be withdrawn, shaped or monetised. Agency that depends on the goodwill of institutions or corporations is not agency at all. True freedom requires the capacity to influence the conditions under which one lives and works – economically, digitally and politically.

I still believe that positive change, if it comes, will emerge more from the ground up than from grand reforms imposed from above. Cities, communities, public infrastructure and shared digital systems remain the most plausible sites for rebuilding balance. Progress in these spaces is rarely dramatic. It is slow, contested and incomplete. But it is also cumulative, and once embedded, difficult to reverse.

History suggests that societies often wait for crisis before correcting course. I hope we can do better. Yet hope alone is not enough. The trajectory we are on actively favours further concentration of power, unless it is consciously challenged and redirected.

The photograph from 1968 reminds me that questioning power is not something one outgrows. It is a responsibility that changes form with time. The tools are different now. The scale is larger. The consequences are sharper. What remains constant is the need for each generation to decide whether it will accept inherited structures as inevitable, or treat them as unfinished work.

The future will not be determined by technology alone, nor by ideology, nor by nostalgia for earlier models. It will be shaped by whether those who follow are prepared to take up the task of reclaiming agency – patiently, persistently and with a clear understanding that democracy, in any meaningful sense, is never finally secured.

Paul Budde (at the start of 2026)